Schmidt raised his field glasses and scanned the plains of hell. His dreams of wandering the world and seeing its sights had to come to this. A sea of mud, craters filled with water, dead men broken into pieces like discarded toy soldiers. Smoke blotting out the horizon on one side, while, elsewhere, the colours of the sky were strange, unnatural. And the wind carried the cries of the dying.

Schmidt still wondered what it was they were fighting for. He didn’t believe the newspapers back home, or the pronouncements of the generals or the Kaiser.

“Willi!”

He glanced down from the parapet of the trench. Hauser was standing below with that glazed-eyed look of his. “Do you hear it?”

Schmidt took a deep breath and descended. He forced down the urge to snap at Hauser. The boy belonged in a hospital. Even if his body wasn’t broken, something in his mind was. “Hear what?”

“That singing.”

Vogel, who had been sitting further along the trench, smoking, got to his feet and wandered over. “What singing?” He made a great pretence of cocking his ear. “No singing, except for the singing of the guns over there.”

“Women singing.”

“Here we go,” Vogel muttered.

“I can hear the sound of women singing. Do you think they’ve got a choir over there? Nurses maybe?”

Vogel jabbed a finger against Hauser’s temple. “It’s you, my friend. Your head’s kaput.”

“Leave him alone,” Schmidt said. He took Vogel’s arm and marched him a few steps down the trench.

“You know it’s true. He’s hearing imaginary voices.” Vogel looked back and froze. “Don’t be a fool,” he cried, and suddenly he was pushing Schmidt away, running back to Hauser who was on the parapet, attempting to climb over the top.

“I can hear them. They’re over there. In that crater.”

Rifle fire erupted from the enemy lines.

“Get down!” Vogel yanked his foot, catching him as he hit the trench floor. He began slapping Hauser’s face. “There’s no one singing. It’s all in your head. Next time you try a trick like that, I’m letting you go over.”

Hauser sat up, dazed. Vogel walked away, cursing under his breath. For a time Hauser was silent. Schmidt would have offered him a cigarette, but the boy didn’t smoke. All the same, Hauser had a silver cigarette case in which he kept photographs of his family. He also had a letter folded up inside, which he’d written in case of his death.

Schmidt remembered the afternoon Hauser had laid out his photographs on a table in the shelter, gazing on them for a long time before he’d begun writing. He’d hidden the paper behind one hand as he wrote, the tip of his tongue protruding from his lips. Just like a child. Which was what he was, really. Schmidt at least had lived a little and seen something of the world. Hauser had been nowhere before this.

Schmidt often thought of the games he’d played as a boy. The games all these men in the war had once played: pretending to be soldiers and fighting mock battles. Listening to old men’s tales of bravery and honour.

His own father still fondly recalled his childhood memories of the great victory parade in Berlin on that sweltering hot June day in 1871. Forty-thousand soldiers led by the generals, Bismark, and the new seventy-four-year-old Kaiser Wilhelm I. Tattered French battle flags carried as a sign of victory. And all along the three-mile route, captured French cannon festooned with greenery.

As a boy, Schmidt had been thrilled by his father’s account. Now he turned away from Hauser and spat into the ground.

Somewhere down the line, Vogel and another man began singing in high-pitched voices.

The boy didn’t seem to notice, but the noise was getting to Schmidt. “Shut up!”

Vogel and his friend burst into laughter.

Schmidt turned his attention back to Hauser who looked at him earnestly.

“I did hear them. It’s not my imagination.”

Schmidt sighed and squatted down beside him.

“I’ve never heard anything like it, Willi. Have you heard of the Lorelei? It’s like her, but more than one. Voices so beautiful, you’d do anything to hear more.”

“Are you hearing them now?”

The boy shook his head. “They’ve gone. But they’ll be back.”

It had started a few days before. Schmidt had seen men lose their minds temporarily, or even more profoundly. So that even if the war ended tomorrow, they were too far gone to ever recover.

Now, night fell, and from behind the lines large cooking pots arrived, their contents dished out for the hungry men. Hauser sat close to Schmidt, eating quickly. Nearby, Vogel complained about the food.

“Sausages,” he sneered. “You call these sausages?” he asked the man in charge of one cooking pot.

“I’ll tell you something I’ve seen,” Hauser said, leaning closer to Schmidt.

Seeing the look on the boy’s face, Schmidt tried to keep his expression neutral, fearing that whatever was about to come out, it would not be rational.

“I saw them.”

“Who?”

The boy glanced around as though fearful of others overhearing. “The women,” he whispered. “I saw them. They were tall and they had beautiful long hair and dresses the colour of jewels.”

“Where?” Schmidt enquired, cautiously.

“One time at night, when I was laying barbed wire, I heard them. So I crawled over in the direction of the singing and, when a flare went up, I saw them. A group of women, all gathered round a crater, staring into it. I wanted to go to them, but a shell exploded somewhere, and when I looked back at them, they were gone.”

“Hmm.”

“You don’t think they came out of one of the craters? In the shelter, I hear voices through the walls sometimes. Coming from inside the ground. I try to listen, but I can never make out what they’re saying.” Hauser fell silent.

Schmidt wasn’t sure if the younger man was waiting for him to respond, or just lost in his own thoughts. “Well…,” Schmidt began.

“You don’t believe me,” Hauser said. “I won’t say any more.”

Schmidt thought that was probably a good idea.

Maybe it was the longing to see a woman, because Schmidt awoke the next morning from dreams of sweet singing coming from inside the walls of the shelter. It had seemed real enough in the dream. “There, you see?” Hauser had said. “I told you so.” The walls were made of soil, not concrete, and they dug through with their hands. The voices beyond became louder. Schmidt scooped and clawed at the mud more frantically, even more determined than Hauser to see what lay on the other side.

Just as his hand passed through, he’d woken up.

Guns rumbled in the distance like thunder. Here, there had been no movement back or forth for weeks. What had all this digging in really accomplished? It could go on forever, if they could find enough men to replace the dead and the ageing.

Vogel had taken to making obscene jokes about the Kaiser, which Hauser took great exception to. His earnest belief in authority and royalty was beyond Schmidt’s understanding.

In the afternoon there was a brief period of sunshine. Vogel basked in it. “Ah, I think I’ll go for a swim later. Fancy a picnic?” He took a puff on his cigarette. “You know, there’s something to be said for this imaginary business.” Vogel opened one eye and studied his forearms. They were blue-grey with mud. “Think I’m getting a tan.”

Schmidt ignored him. Instead, he watched Hauser who sat perfectly still, head cocked, as though listening for something. For a moment, Schmidt listened too, but he could hear nothing but the distant rumble of guns.

In the following days, the enemy bombarded them relentlessly day and night. The German artillery returned fire. When the warning came of a gas attack, they pulled on their masks. Clouds swarmed over them. Someone brushed past Schmidt. He turned and managed to make out the figure of Hauser through the thick gas, running away.

Schmidt stumbled after him, occasionally tripping over men. It was here in the trenches and craters that gas stayed longest.

There was a fresh explosion to his left, over the parapet.

He hit the ground. Mud rained down on him.

The gas still hung, but the wind was picking up. He heard choking. Nearby a soldier, bare faced, coughed up blood. He got up to help the man only to hear a whistling overhead. He hit the ground again and the shell exploded. When he looked up, the soldier was dead, though his eyes stared all the way to the heavens.

Schmidt got to his feet and walked slowly down the trench. There were dead men, unmasked, lying down this way, and others who had pulled on their masks in time only to be blown up by a shell. He rolled corpses over. None were Hauser.

Ahead, through the gas, a soldier stood gesturing to a shadowy figure by the trench wall.

Schmidt knew instinctively that the soldier was Hauser.

He stumbled towards him. The boy turned briefly, wearing that terrible mask their lives depended upon, before stepping into the wall of the trench.

There was no other way to describe it. A black hole, the height of a man, had opened up in the trench wall where the figure had stood just moments before. And then both Hauser and the hole were gone.

“What happened to Hauser?” Vogel asked later, once they had the all-clear to remove their masks. “Where is Thomas?”

“I don’t know. I lost sight of him.” Schmidt had searched that section of trench, pressing his hands into the trench wall. He’d walked further along to where the entire trench had caved in under shelling. Hauser was nowhere to be seen. He was now among the missing.

A week later, they were back behind the lines. They could hear the war, miles away, and they saw the evidence of the devastation in the stretchers carrying the injured and the dying. The hospital trains were full. Vogel had fallen into a sullen silence since the boy’s disappearance, punctuated only by a half-hearted flirtation with a nurse. Like Schmidt, he’d seem many of his friends die. There were few of their original company left. Hauser had been a newer recruit, arriving on a troop train on which someone had chalked: Fresh Meat Consignment, Courtesy of Ludendorff and Company.

You have to feel nothing, Schmidt thought, and yet to feel nothing is to lose the one thing you have left. Your humanity.

He carried the image of Hauser writing his last and final letter. Schmidt had it now. The boy had left it with his things in the shelter. But Schmidt couldn’t bring himself to mail it. The boy could be alive.

On the second day behind the lines, as they sat playing poker, their corporal stopped by to report that Hauser had turned up, badly injured, but alive. They would find him in the hospital. Schmidt and Vogel threw down their cards and tore out into the pelting rain.

The hospital smelled of carbolic and death. Hauser lay in the bed nearest the door, waxen faced. He had a dressing on his cheek, held in place by a bandage. His eyes were closed, but they flickered open when Schmidt brushed the back of his hand.

“Hey, Thomas! What happened to you?” Vogel tapped his arm gently. “I tell you, we thought you were a goner.”

The boy frowned, staring over Vogel’s shoulder. “I don’t remember.”

“You’ve been out there all that time?”

“I don’t know.”

Vogel shook his head. “You must have been knocked out for a while.”

“Yes,” Hauser said. “I must have been.”

“Still,” Vogel went on, “it’s a miracle. And it calls for a celebration.” He chatted on, giving the gossip he’d received from home, and promising to sneak some drink in. After a while, Hauser’s eyes grew heavy.

“We’ll go now,” Schmidt told him. He wondered how badly hurt the boy was.

“But we’ll be back,” Vogel promised.

Outside, they found an orderly and questioned him. “He’s been shot full of holes,” the man told them. “It’s a miracle he’s lasted this long.” He paused and added, “They say he’s a deserter.”

“That’s a dirty lie,” Vogel hissed.

“Still, he was found quite a distance away. Just warning you.”

That night, as Vogel and some of the men got drunk, Schmidt slipped back to the hospital block.

The boy lay on his bed, sleeping. Around him, men sat up, staring into space, while others lay unconscious. A group, some with missing limbs, played an intense game of cards. Schmidt lingered by the bed, wondering whether to wake Hauser up or come back tomorrow.

The boy’s eyes flickered open. “Did you send my letter?”

“No,” Schmidt admitted. “There was always the chance…” He paused, sitting down on the edge of the bed. His voice dropped to a whisper. “I saw the hole in the trench wall, Thomas. I saw you walk through.”

Hauser said nothing.

“I’ve heard the singing too. You were right.”

There was a long silence. Then Hauser said slowly, “The corporal thinks I ran away in panic. He thinks I deserted the unit.”

“But you and I both know that isn’t true.”

Hauser beckoned Schmidt closer. “When the gas came, I thought I saw one of the women walking through the trench. I followed. I wasn’t thinking of deserting. It never crossed my mind. I swear.”

“I know.”

“A black hole opened up in the trench wall. She stepped inside and waved her hand for me to follow. And I did. When I looked back over my shoulder, the trench, the gas, the whole war was gone. There was light ahead too. I tore off my mask. We came out into a garden,” Hauser said, eyes shining. “Willi, I never saw such a place. There was a kind of rose, bigger than we have back home, and red as red can be. There were trees in bloom, and the sky was clear blue. No gas, no shelling. No war.” Hauser lifted one hand from the sheet and pulled on Schmidt’s sleeve. “Do you believe me?”

“I believe you, Thomas. What I wouldn’t give right now to see a place like that.”

Beads of sweat had broken out on the boy’s forehead, but he smiled. “She was taller than any woman I’d ever seen, and it was as if a light shone out of her. I think she was the queen of that place. She made me think of my mother and my sister and a girl I promised to marry after the war.”

Hauser fell silent, eyes closed. Schmidt wondered if he’d fallen asleep. He waited patiently and, after a time, the boy’s eyes opened and he continued.

“‘I never saw gardens like yours before,’ I told her. ‘Or flowers. The roses are so red.’” Hauser frowned. “She looked sad then, Willi. She said, ‘Yes, they are, but they shouldn’t be.’ I didn’t know what she meant. I stepped closer to one of the rose bushes and that’s when I saw it. I’d thought the roses were red, but they were white. Blood made them red. It dripped onto the petals and the leaves, and onto the ground. And there on the ground lay hands, arms, legs, like we see on the battlefields. The bodies and the blood had passed through the mud and fallen on that place.

“She talked of the red rain that falls sometimes. She showed me places where the flowers and the trees were dying.”

Again, Hauser closed his eyes and fell silent for a few moments, before going on.

“That’s why they sang. To distract the armies. Otherwise, she said, they would howl and grieve for what was happening to their world, but their howling would only sound like the wind to us. So they sang instead, but only a few men could hear their songs.”

He swallowed. “I knew then that I had to go back and tell someone. Tell what she’d told me. She pointed to an archway and said if I wanted to leave, to walk through it.” His voice was becoming hoarser now. “I looked at her long and hard, and then at the garden around me. Beyond, I could see mountains, and a glittering sea. A part of me wanted to stay, but I said goodbye and walked through. Right into gunfire. I fell. I’d been hit. The sky was grey above me. And there were no flowers. Just the old rotten smell of the battlefield. I crawled towards a trench.” He shook his head. “Everything went black. Next thing I knew, I was here.” He paused, licking his lips. “You do believe me, don’t you?”

“I believe you.”

The boy was lifting himself from the bed, straining towards Schmidt.

“It’s all right, Thomas, I know it’s all true.” He pushed the youngster back gently. The boy’s eyes were closed now. Schmidt waited for him to speak again, but he remained silent. Schmidt got to his feet.

“Wait,” Hauser said, opening his eyes. A tear ran down his cheek. “Willi, make sure you send my letter this time. And tell them I didn’t run away. I’m not a deserter.”

That night Schmidt heard the singing again for the first time since they’d left the frontline. When he woke, it was to the news that Hauser had gone missing. Somehow he had managed to get himself out of bed and walk right out of the hospital. A search was made, but the lad had vanished off the face of the Earth.

“I thought he’d died and the body had been taken out when I wasn’t looking,” a medical orderly told Schmidt. “But even the other men on the ward say he was there one minute and gone the next. Nobody saw him go.”

“Nobody noticed anything odd at all?” Schmidt asked him.

“Unless you count the scent of roses odd. But in amongst the gangrene and the carbolic, who is going to complain about a smell like that, eh?”

They were two days back in the trenches when news of the advance came.

“Have you heard?” Vogel asked Schmidt later. “We have an appointment with some British beef. Corned beef, I tell you! We’re going to take some enemy trenches!” He paused. “Hauser is lucky. Lucky to be out of this. To die peacefully behind the lines.” This was how Vogel imagined the boy’s end. “What else can a man wish for? Except his own bed, and a good meal, and his family, and to know he’ll never again have to live in a trench, or pick up a gun, or kill another man who’d also rather be home with his family.”

“You’re getting sentimental.”

“I say we shoot the officers and join the other side.”

“Shut up.”

“Actually, I say we shoot the officers, send a message to the other side to do the same. Then we can all get together to make a new side.”

Schmidt liked the sound of that.

“Hey,” Vogel tapped his arm and leaned forward. “You didn’t really hear women singing did you? You can tell me.”

Schmidt paused, then shook his head. “No, but I would have liked to.”

Vogel seemed disappointed. His gaze moved along the top of the trench. Then he turned away.

When the command came, Schmidt took a deep breath and climbed over. Clutching his rifle, he ran across the mud, dodging craters.

Men ran ahead. Vogel was to his right. They ran clear. No one fired on them.

Schmidt had a mad thought. Perhaps the other side had come to their senses and gone home. Perhaps the war was over, but no one had told them.

But a shell tore through this idea.

The limbs of men flew through the air in front of him. Rifle and machine gun fire opened up.

Schmidt dropped to the ground, aware he’d been hit. Vogel slowed down, looking back. In the next moment, Vogel jerked, falling face down in the mud.

A bolt of pain shot through Schmidt’s arm and shoulder. He dragged himself along the ground towards his comrade, calling his name over and over again.

There was no answer.

When Schmidt reached his friend, he was dead, staring into the next world. Reaching out with his good arm, he gently closed Vogel’s eyes.

A soldier leapt over them and carried on running for the enemy lines. Schmidt took a last look at Vogel before crawling, teeth gritted, towards a crater. He slid inside as more men ran past. Machine gun fire tore up the mud.

The bottom of the crater was full of water. The body of an enemy soldier lay half submerged. Schmidt prodded him cautiously with his rifle butt and the man let out a long whimper. How long had the soldier been trapped here, left to die, too weak to alert a search party?

Above them came the pounding of the heavy artillery.

Schmidt carefully turned the soldier around. Then he moved away and they stared at one another for the longest time.

Eventually, darkness fell. Occasionally a flare went up. But night was still the best opportunity to get back to the lines. He could crawl back or try to alert one of the search parties sent out to scout for the wounded. Perhaps the other fellow would try to get back to his side too. But Schmidt sensed the man was too weak.

Under the green light of a flare in the night sky, Schmidt drew out his field dressings and held them up for the soldier to see. He approached the man cautiously through the muddy water. He was an older man, someone’s father, just young enough to be here and no more. “Can I help?” Schmidt asked him in English. The soldier shook his head. They were plunged back into darkness.

For a long time they were silent. Then the man said, “Would you like a cigarette? I don’t have anything to light it with.”

“Neither do I.”

The stars turned overhead. The night was bitterly cold. The water around Schmidt’s legs felt like ice.

“Are you badly hurt?” Schmidt asked.

“It’s my legs, mostly.”

They fell silent. The wind was blowing across the fields of mud. Schmidt thought about his fallen comrades: Vogel and Hauser and all the rest. He thought about his family, his mother and father and sister, far from here.

“Do you hear that?” the man asked.

“Hear what?”

“Nothing.”

Schmidt listened. Underneath the howling of the wind, he could hear it, the choir of voices, singing. “I hear it now. Women singing.”

“It’s coming from inside the mud,” the soldier said. “I’ve heard it before. Nobody believed me.”

“I’ve heard it. I knew another man who heard it.” Schmidt paused. He put his ear closer to the wall of the crater.

The voices were getting louder, closer.

“I could tell you a story,” he said, “about a soldier who passed through the mud to the other side, who met one of those women. But if we stay here, we’ll be dead by morning. We should try digging our way out of here.”

“Digging our way to where?”

Schmidt looked into the darkness of the mud around them. “I’m sick of this war,” he said. The fingers of his good arm sank into the earth, and he began to dig.

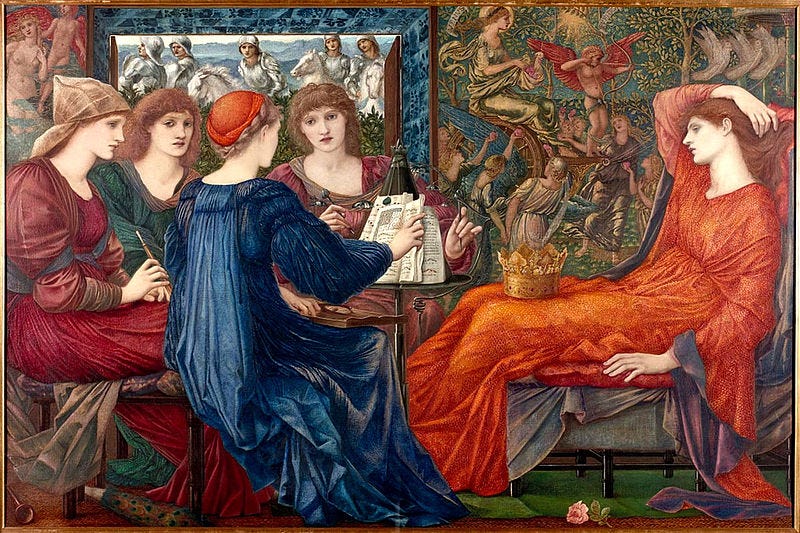

The artwork illustrating this story is public domain in the UK and US and most other places since the artist is long dead. The works are Laus Veneris by Edward Burne-Jones, The Mirror of Venus by Edward Burne-Jones, and The Prince Entering the Briar Wood by the same artist. The images are from Wikimedia.

Love the way you arched the story and the elements of magic realism! And that no matter which side you were on, war was war…

This is such a fantastic piece!