When I awake, I’m naked, wearing only my watch and a pair of antique stockings secured with pink ribbons. I wasn’t wearing the stockings when I went out last night. My clothes are nowhere in sight.

Daylight streams through tall windows, falls across my skin. Caress of heat.

I’m lying in a room with almost no furniture, lying inside a huge gilt frame, against a pool of white silk ripped from undeserving casements. There’s a wine bottle in the bottom left corner of the frame, near my foot. Candles stand on the floor, wax pooled around their bases.

I’m starting to remember.

Last night I was in a bar. I was in a few bars if truth be told. I’d been persuaded by friends to join them in a pub crawl around Prenzlauer Berg and Mitte districts. I’m not much of a drinker, and when I do drink, wine is my beverage of choice. It can be red or white, but last night it was a beautiful red. I know nothing about wines, but this one entranced me. I swirled it around in the glass, held it to the light, breathed in the scent.

That was the moment. Right there in that bar in Mitte.

She appeared from the crowd, a colourfully dressed brunette. She stood over me, one hand on her hip, lips curved. I didn’t invite her to sit. She invited herself.

None of my companions acknowledged her at all.

She sat down and immediately launched into an account of an eighteenth-century Viennese woman, a lesbian aristocrat and art collector with a marriage of convenience and a string of women. After seducing the wife of a powerful man, this aristocrat was obliged to find a reason to go travelling, and had come to the court of Frederick II where she secretly took up her old pastime.

“And this pastime,” I said. “Was it collecting art or collecting women?”

My new companion offered no reply, just a smile. Then she took up her story as though I’d never interrupted. She mentioned a place. The Gallery of Earthly Delights. Her lips were the colour of wine. If I let her sip from my glass, they’d taste of wine too.

She ended her account abruptly, got up and left, vanishing into the growing crowd. I tried to look for her, but she’d gone.

My friends suggested we move on to a club. We piled into a taxi. I half expected to end up in some Weimar cabaret-themed place, which had happened on a previous occasion, but this time our journey took us outside Berlin.

When we arrived at our destination, we were enveloped in the dark cloak of night. Hand in hand, we stumbled between trees, emerging onto the wide driveway of a great baroque house. Each window glowed. When the doors were thrown open, a man in eighteenth-century costume bowed and took our coats. His face was powdered and he wore a white wig.

I don’t know when my companions left me. It was very soon after our arrival. They were there, they were gone.

Alone, I walked from candlelit room to room, hollow chambers where my voice echoed and the doors ahead opened one after another. Each time I passed through, there was no one there, no powdered, wigged man waiting to bow. No one at all.

And yet there was someone.

For as the doors opened and the corridor of chambers stretched before me like a gallery, I saw the final room glittering in a galaxy of candles. A woman stood waiting, her hand outstretched, beckoning, her long skirts whispering among their folds.

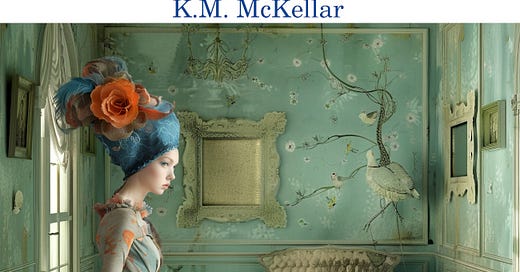

Now, alone again in the light of day, I look around. Frames hang on the walls, but no paintings hang inside them. Instead, frames hang within frames.

Looking at the stockings, I try to remember what I was wearing last night, but my life beyond the present seems increasingly vague.

I get to my feet, pass from empty room to empty room. Whispers sound around me, the odd quiet cough, a footstep, but like the hands that opened the doors last night, these people are invisible.

I ought to cover myself, but the thought is a reflex. Comfortable in my skin, I wear the marks of last night’s kisses and caresses like the finest figure-hugging dress.

Walking through the house, I see more empty frames, but increasingly there’s a painting inside, always women, always nude. Only hairstyles, jewellery, or some other accessory, betray each painting’s era. Some rooms contain a piece of furniture, ghosted by a white sheet. A peek underneath reveals Louise XIV, Biedermeier, the clean utilitarian lines of the Bauhaus. In the corner of an upstairs chamber, there’s a browning leaflet on the floor. Bending down to pick it up, I see it advertises a Dada exhibition, long gone now, ninety years ago.

When I find her, it’s at the end of a long gallery, where she stands, one hand on her hip, lips curved, skirts sweeping to the floor.

Canvas without a frame.

I could leave now, find my clothes, the way out. Instead, I return downstairs to the footsteps and whispers.

I know that under her painted dress she is bereft of stockings.

They adorn me now, like the frame.

I wrote this piece of flash fiction many years ago, and I think it may have come out of an idea to play around with irrealism. However, whether it would work that way is another matter.

Very evocative. Very sensual. Very nice.

Ooh, this is such a sensual dreamy piece!