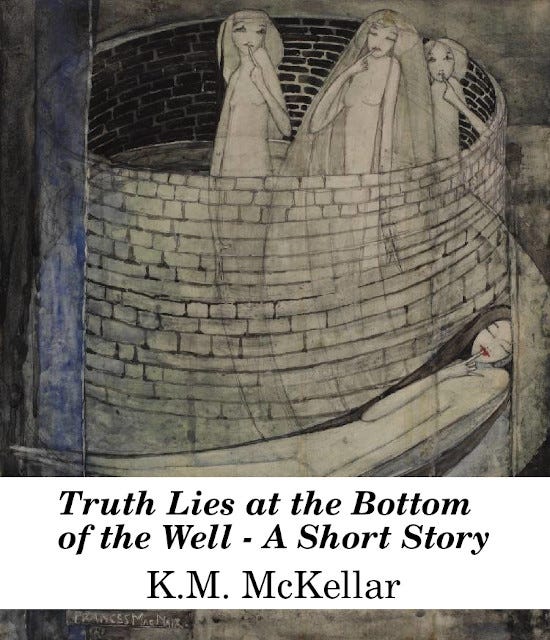

Truth Lies at the Bottom of the Well

Standing at the window, looking at the sunset between the tenements, I’m attending a funeral of sorts.

Standing at the window, looking at the sunset between the tenements, I’m attending a funeral of sorts. Not the passing of the day, but the passing of something else.

“Why won’t you speak to me, Frances? Why this silence?”

Behind me, a watercolour dries. A woman with her finger to her lips. Around her, symbols of marriage and motherhood.

“What’s the matter with you?” Bertie asks. He smells of drink.

Hugging myself, I turn and walk into the hall. Years ago, our son, Sylvan, couldn’t sleep without the door left open. Older now, his door is closed. Turning the knob, I go in and stand over him. His breathing is slow and regular. Outside, beyond the curtained window, the clip-clop of horses’ hooves, the clattering wheels of a coach, the horn of an automobile, they pound in my head, puncturing the silence there.

I’m bent over, hand to my stomach. From my mouth bursts flowers, birds, faces from my paintings. A trail of these images lies on the ground like a path that wanders away. My mouth is full of pictures. My brush is my tongue. I’ll speak in sweeping strokes. I’ll write my words in mauve, green and blue.

Waking in the darkness, I gasp for breath. The clock on the wall ticks on.

My pulse slows. Falling back into sleep isn’t easy. There’s nothing worse than lying awake listening to the peaceful rest of a man one loves but has also come to hate.

Best to get up.

In a cupboard in the hall, there’s an old trunk. It contains the past, those things that haunt us in the dead of night. Old ghosts.

Lighting a lamp, I go now to confront them, because that’s all one can do. It’s not possible to flee them. They always catch up.

The trunk opens on an old notebook of Bertie’s. On the inside cover he’s inscribed his name, James Herbert MacNair. Leafing through the pages, I find designs for furniture, mirrors, posters. My notebooks contain sketches, designs for clocks, mirrors, candlesticks, picture frames, much of it done years ago at the art school or the Hope Street studio I shared with my sister, Margaret.

I find a preliminary sketch for Ill Omen: Girl in the East Wind with Ravens Passing the Moon. Hands clasped before her, the girl stands, perfectly alone, her silence unquestioned. I finished the painting almost twenty years ago. When I was still Frances Macdonald. Before Frances MacNair was born.

A sheet of paper slips to the floor. A painting by my son. I remember the day he brought it to me, nearly four years ago, shortly after we returned to Glasgow. Sylvan appeared as I sorted through the trunk. He wanted to look at my pictures and asked me to look on his.

“This is you, Mama,” he told me, pointing to the woman with a paintbrush in her hand. “And this is Papa.”

Papa too had a brush. Looking at the picture now, in the lamplight, I see it sticks out his pocket.

“And that’s me,” Sylvan went on, pointing to the boy in the middle.

Except that he doesn’t stand in the middle. Papa stands off to the side, looking away, and Mama, though closer, doesn’t look at the boy either. The boy looks at her, though. He tries to take her hand. But Mama’s hand holds a paintbrush.

It’s not that I don’t love my son. But without the brush in my hand, I can’t speak, I can’t breathe. Without the brush in my hand to paint my pictures, my throat would fill with images and I’d choke to death. Man Makes the Beads of Life but Woman Must Thread Them. It’s not possible to be a good mother and a good artist, so I will be neither.

When I fell in love, all those years ago, I saw the choices ahead, difficult choices. I didn’t anticipate how quickly success would flow away.

Like drink poured down a drain.

In the lamplight, I eye the coat hanging on a hook on the wall. He likes to keep a flask in the inside pocket. I get up and fetch it, returning to my spot in front of the cupboard.

At least we’re no longer living with Margaret and Mackintosh. We have our own home again, and it doesn’t have the cool perfection of their flat, where everything’s so pristine, never meant for a child to play in. Bertie painted a mermaid frieze when we moved in here, in remembrance of happier times. Perhaps he thought he could paint the happiness back.

I take a drink from his flask. The whisky burns its way down to my stomach.

Poor Charles, he loves children, but Margaret never had any. Let his buildings be his children. They’ll live longer, and never need to be fed or clothed. They won’t cry in the night and get him out of bed. They’ll stand until he’s dead, and long after that, unless someone comes to knock them down. No, instead of children, Margaret has given Toshie two Persian cats, who curl up on their cushions next to the fireplace, and like everything else, fit in perfectly.

In the trunk there’s a sketch for a painting I planned to work on a year or so ago. ’Tis a long path that wanders to desire. There she stands, the woman with my younger face. Her hair flies out, merging with the winding paths behind her. There are two figures. One turned away, and one looking forward. Both naked, both standing behind her. She holds her palms up, uncertain about some choice she has to make.

The man whose face is seen, I married.

The one turned away is the one I never met. Or the one I walked away from. Or the one who broke with me. On the path I have to pass him to get to the other. More and more these days, I wish I’d never passed him, or if I had, that I’d taken a different path.

In the light of morning, he examines my latest painting. “You’ve lost your touch,” he says. “Some talent flowers early, and that’s how it was for you. For us both,” he adds with a bitter laugh. “Isn’t that right, my little France? Married life, eh?”

Later he comes, smelling of beer, jacket buttoned up to the neck, tennis shoes wet from the rain. There’s a trail of footprints on the floor. He’s seeking forgiveness. “I can’t stop thinking about the old days, Frances.” He steps a little closer.

I don’t move away.

“I didn’t mean it about your painting.” He’s stooped, lost, in search of hope. “You do still love me, don’t you Frances? Tell me the truth.”

I don’t answer. Instead, I stand on tiptoe, take his face in my hands, and kiss his cheek.

When I was a child, I played near a well. I liked to drop stones inside. That way I could mark its depth. I hung over it, and called down my name, threw in branches, leaves and flowers. I dreamt about the well. And I began to see that the well contained my dreams. The images lay down there in the silence. If I’d had a bucket, I could have dropped it and scooped up some of those dreams. I could have pulled the bucket up and poured the images over myself, drunk from them.

One day I took a rope, tied it to a tree and climbed down into the darkness. I already knew there was no water there. This was a well that contained more precious things. For a time, it contained me, until my sister came to look for me. When I looked up, I saw her womanly shape, the fiery red glow of her hair. My voice echoed all around.

I’d sat in that well for hours. Dead flowers surrounded me, and new ones, recently thrown down. I sat and dreamt. I dreamt pictures, pictures I’d already painted and others I still meant to do. Now Margaret called for me to climb up. Should she fetch help? Could I climb up myself? She disappeared.

I was left in the silence again. I took the rope in my hands and climbed up, booted feet finding footholds. I didn’t think about falling, or striking my head, or dying. The future lay ahead.

I was still immortal.

I climbed out and sat on the rim, waiting for my sister.

Frances Macdonald was the younger of a pair of artist sisters whose work is associated with the Glasgow Style. Charles Rennie Mackintosh was the most famous member of the movement. He married Margaret Macdonald, while his friend James Herbert MacNair married Frances. They were known as The Four. The opening image, Truth Lies at the Bottom of the Well, is from somewhere between 1912 and 1915. Frances was the first of the four to die, in 1921. This places the image in the public domain in the UK and US and other countries. The image was obtained from Wikimedia Commons. The US public domain tag is as coded below:

{{PD-US}}